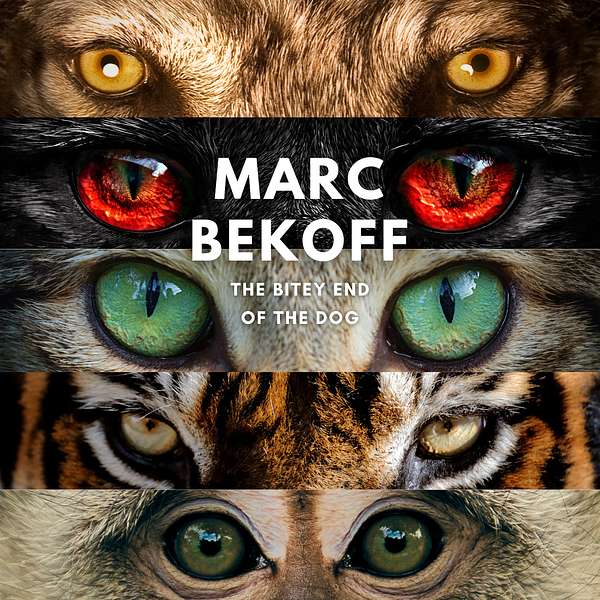

The Bitey End of the Dog

A podcast dedicated to helping dogs with aggression issues. Michael Shikashio CDBC chats with experts from around the world on the topic of aggression in dogs!

The Bitey End of the Dog

Dog Parks, Dominance, and Deep Dives into Dog Behavior with Dr. Marc Bekoff

Step into the world of canine behavior with the distinguished Dr. Marc Bekoff, a professor emeritus of ecology and evolutionary biology. This episode takes you on a captivating journey as we delve into the emotional landscape of our furry friends, the impact of confinement on their behavior, and the fascinating dynamics of dog-human relationships. We don't stop there, we also tackle the often ignored segment of free-range and feral dogs globally, citing Dr. Bekoff's invaluable experiences with the Jane Goodall Institute and his insightful publications.

We also discuss the controversial world of dog parks, examining the fluid relationships among dogs and between dogs and humans. We debunk common misconceptions about dominance in animals and discuss the misuse of the term 'alpha'. In anticipation of Dr. Bekoff's upcoming book, Dogs Demystified: An A-to-Z Guide To All Things Canine, we provide a sneak peek into the wealth of knowledge it promises. This conversation with Dr. Bekoff is an eye-opening session that deepens our understanding of canine behavior, reminding us to respect their emotions and choices. Join us on this enlightening journey and let's explore the world through a dog's eyes together.

The Aggression in Dogs Conference

The Bitey End of the Dog Bonus Episodes

The Aggression in Dogs Master Course and Expert Webinar Bundle --- LIMITED TIME SPECIAL OFFER

ABOUT MARC:

Marc Bekoff is professor emeritus of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Colorado, Boulder. He has published 31 books (or 41 depending on you count multi-volume encyclopedias), won many awards for his research on animal behavior, animal emotions (cognitive ethology), compassionate conservation, and animal protection, has worked closely with Jane Goodall, is co-chair of the ethics committee of the Jane Goodall Institute, and is a former Guggenheim Fellow. He also works closely with inmates at the Boulder County Jail. In June 2022 Marc was recognized as a Hero by the Academy of Dog Trainers. His latest books are The Animals' Agenda: Freedom, Compassion, and Coexistence in the Human Age (with Jessica Pierce),

The Aggression in Dogs Master Course and Expert Webinar Bundle Offer!

Only 50 bundles will be available. Offer expires October 31st, 2025!

Learn more about options for help for dogs with aggression here:

AggressiveDog.com

Learn more about our annual Aggression in Dogs Conference here:

The Aggression in Dogs Conference

Subscribe to the bonus episodes available here:

The Bitey End of the Dog Bonus Episodes

Check out all of our webinars, courses, and educational content here:

Webinars, courses, and more!

In the season finale of the Bitey End of the Dog, I have the honor of chatting with none other than Mark Bekoff, a true pillar in the world of animal behavior. You're not going to want to miss this episode, as we discuss everything from emotions in animals, sentience, aggression in ethology and even the dreaded D word or dominance. Mark is a professor emeritus of ecology in evolutionary biology at the University of Colorado, boulder. He has published 31 books, or 41, depending on if you count the multivolume encyclopedias, won many awards for his research on animal behavior, animal emotions, compassionate conservation and animal protection. Mark has also worked closely with Jane Goodall as a co-chair of the ethics committee of the Jane Goodall Institute, as well as a former Guggenheim fellow. His latest books are the Animals Agenda Freedom, compassion and Coexistence in the Human Age, co-arthured with Jessica Pierce. Canine Confidential why Dogs Do what they Do. And Unleashing your Dog a Field Guide to Giving your Canine Companion the Best Life Possible, also co-Arthured with Jessica Pierce. And he also publishes regularly for Psychology Today. Mark and Jessica's most recent book, a Dog's World Imagining the Lives of Dogs in a World Without Humans, was published by Princeton University Press in October of 2021. Dogs Demystified and A to Z Guide to All Things Canine will be published by New World Library in June 2023, which is actually probably out by now at the time of this recording and the second edition of the Emotional Lives of Animals will be published in March of 2024.

Speaker 1:In 1986, mark won the Master's Age Graded Tour de France. His homepage is markwithac m-a-r-c. Beckoffcom, and if you are enjoying the buddy and the dog, you can support the podcast by going to aggressivedogcom, where there's a variety of resources to learn more about helping dogs with aggression issues, including the upcoming Aggression in Dogs conference happening from September 29th through October 1st 2023 in Chicago, illinois, with both in-person and online options. You can also learn more about the Aggression in Dogs Master course, which is the most comprehensive course available anywhere in the world for learning how to work with and help dogs with aggression issues. Hey, everyone, welcome to the bitey end of the dog.

Speaker 1:I have a super special guest this week, dr Mark Beckoff and I have been following his work for years I think many of us in the dog training industry have, as well as beyond. I was talking to Kim Brophy yesterday. We were talking about you and we were kind of I was picking her up. I'm like if you were to ask some questions to Mark, what would you ask? And you know, kim is an applied ethologist and she's definitely in the ethology field as well, so she's like you know that's a good question. He's kind of one of the last true ethologists. Is what?

Speaker 1:she called you so much respect to you, mark, and welcome to the show.

Speaker 2:Oh, it's great to be here. I'm thrilled. I like free ranging discussions about wonderful dogs.

Speaker 1:I'm excited for this, so I'd first like to jump into your focuses on ethology and behavioral ecology or evolutionary biology, but I'd love to get your thoughts on for dog trainers or people working with dogs. If you had a new trainer and you're like, all right, this is the sciences that are important to understanding behavior, what would they be for you?

Speaker 2:Oh, wow. I mean, simply put, I would ask them to pay attention to the good science of, say, animal emotions and animal cognition. You know, focusing maybe on dogs, but not really. I mean, dogs are mammals and what we're learning about animals other than dogs is really applicable and sounds unscientific. But the other two things I would stress would be pay attention to common sense and always treat your dog with the most respect you can. They're living sentient beings and they care about what happens to them. If you will, but you know that would be it just weaving in the latest science and common sense. And also and I'm sure you and I will talk about it something I'm really interested in because I'm a field biologist and oftentimes you can see similar studies on the same animals that produce very different results.

Speaker 2:Pay attention to the context of the studies, because it's not that the science is bad, but different dogs are studied in different labs using different methods, data are analyzed differently, so sometimes different labs disagree. It's not because one lab is doing better work than the other although there are differences, to be honest but it's more context, and I've written a lot about this in terms of when I've partaken in lab studies around the world. They're all good, but you know, every now and again somebody comes in and says, oh, my dog had a bad day. Should I partake in the experiment? And I always say no, but talk to the person doing the experiment.

Speaker 2:Or you know, one woman came in to a place where they're using food as a reward and she was running late, so her dog had just eaten. And I'm not saying that that's good or bad, it's more, it can influence the results. The other thing is pay attention to the fact that really 75% of the billion or so dogs on the planet are free ranging or feral on their own. So a lot of the data that come from studies in labs come from home dogs and there are there's a lot of similarities. But sometimes people will say, well, dogs don't do this or can't do this, and and I've seen what they're talking about countless times, even at just free ranging dog parks. So I mean just being careful about how we use the information.

Speaker 1:Yes, and I love that you mentioned. You know the vast majority of dogs on the planet are not in a pet home, right? They're free ranging or you know they're out on the street somewhere and so I talk about that a lot. I mean, there's so much we can learn about seeing those dogs in that environment, but what behavior to expect in dogs in most cases, and then we put them into home environments and just how much that environment can impact their behavior. So how much would you say we should separate that when we're looking at it, or should we really be looking at much more of these, those free ranging, feral or whatever category of dog you want to put them into? But how much should we be studying those dogs to apply to pet homes? Or should we, because there's such a significant environmental difference and then we can get into the rabbit hole of certain breeds that we're selecting behaviors for that are more likely to be in a home environment.

Speaker 2:Yeah, that's a great question, I mean. The other big message, of course, is that there's individual differences, even among dogs when they you know, when their eyes open. I remember when I did my field work on coyotes and I've also seen wild wolves when they come out of their den at three weeks of age. They're very, very different personalities. There's bold animals, there's shy individuals, there's some who are so obnoxious you hope you never see them again. You wish them well, but your questions are really good one.

Speaker 2:So I think what we really need to do is take into account the context in which these studies are done Are they home dogs, are they in labs, are they at dog parks or free ranging and pay careful attention to how data were collected.

Speaker 2:And this is not to be over scientific, it's just more to say, it's an evaluation of what the results mean. But I think the big question of who dogs are, you know they all have the same common wolf ancestor and what their behavioral potential is, their cognitive abilities, which simply means how they learn certain things and use that information to adapt to different situations, and also their emotions. But also, you know, people say, well, you know, male dogs aren't good fathers, but we don't know that really for captive animals, because usually the male isn't around and there are field studies showing that there is paternal as well as what we call allopaternal behavior, where there are helpers, you know, who help raise the children of the female who gave birth. That's what I find the most exciting. I mean, that question is the most exciting to me because it shows that there's no the dog, there's no universal dog, and when it comes down to training or teaching them or educating them, what we want them to do, taking into account individual differences in personalities is really important.

Speaker 1:Yes, definitely, definitely. So taking a step back and looking at all of that that you're saying, you know, from an ethology lens, you know, I think sometimes we need to help pet owners or pet guardians understand, you know, the natural behavior dogs and then when we tried to put that into the home environment or very restricted environment, how much that can impact things from an enrichment standpoint. Can you talk us through that a little bit and why it's important against really, yes, it's important to look at the individual dog but as well as all the factors that can influence behaviors from that ethology lens.

Speaker 2:Yeah, that's a great point, Because oftentimes the dogs don't have the opportunity to express their, if you will, behavioral potential. They're so accustomed to being what I call helicopter. They're always told no, don't do this, don't do that, you know. So they get to the point where they don't even try. They may be bored, they may be just sort of what's going on in their mind could simply be look, you know, I don't feel like partaking in this experiment and I had some very well known primatologist tell me some years ago that he thinks that when you're looking at great apes and monkeys in the lab, sometimes they just don't do something because they're bored or they just don't feel like doing it.

Speaker 2:It's not because they can't and other field primatologists have seen these behavior patterns that you can't get these captive animals to do, you know, in the field. So I think that that's really, really important. But it all comes back to knowing the dog as an individual, knowing their personality, knowing what they've been exposed to, knowing what they like and don't like. So once again, I think the exciting thing for me in the future in dog research is paying attention to all those variables and once again I stress that the science that's done among captive animals. You know, sometimes people go into homes and watch the animals. Sometimes they're in labs. It's not bad science, it's just extremely limited science, and my own experience doing field work on coyotes and other animals is they too. When you watch them in captivity they're interesting, but they're not often able to express their full behavioral repertoire.

Speaker 1:And I would love to kind of expand on that, Since the podcast is about aggression in dogs. I'd love to pick your brain on, you know, because you have such broad experience seeing, you know, studying animals and their natural violence versus captivity. And then we see dogs and in my experience, dogs that are, you know, not owned by somebody or not in the confined environment, are less likely to display aggressive behaviors than we're seeing in home environments, especially environments in which they're much more controlled and restricted and sort of the nature of aggression cases. We're often asking for more management, more restriction to prevent the dog from biting anybody. So the dogs created more or less walks happen. So can you expand on that? Just sort of a broad overview of what your thoughts are? I'd love to go inside your brain.

Speaker 2:Well, yeah, I mean across species. When animals, individuals, feel trapped, which could be leashed, tethered, confined in a room, they get more assertive or more aggressive, sometimes fear based. They're just afraid they can't get out of a situation. So I think those concerns are really true and you know you've probably heard as well as I have, although I can't find a single controlled study that you know leashed dogs are more assertive or aggressive and when they're awfully leash, they're fine. I think part of it is that they feel free and they're happier. But I think part of it is they feel more in control of what they're able to do. You know, if another dog jumps on them and they're not sure whether the other dog's intentions are to play or to dominate them or to be assertive, when they're free to get away and not trapped, they don't have to respond to what would be the most adaptive response if they're tethered and trapped would be to be aggressive.

Speaker 2:And you see this in wild animals. I've seen it in wild coyotes and wolves and foxes where when they're pinned against the wall although there may not be a wall but there's no way out they express themselves in different ways than when they can just feel free to leave, and oftentimes just leaving a situation is really the remedy. The other animal goes okay, you don't want to play, okay, fine, you don't want to fight, okay, fine, okay, you don't want to do what I want to do, fine, and they'll find someone to find another dog, in this case, to do what they want to do with them.

Speaker 1:Yeah, the buzzword right now is agency or choice and control on the environment. Is that kind of? What you're speaking of is being able to make choices in the environment.

Speaker 2:Absolutely. It comes down to what people call agency Freedom to make a choice. And then the other side is that you know your choice to do certain things will be honored. But if it's not honored that's when I say that's okay, it's not okay. But if it's not honored and you're free to get away, then you don't have to worry about being, if you will, pinned against the wall and forced to do something that you might not want to do.

Speaker 2:I mean, wild animals really are very good at avoiding, if you will, interdog, inter coyote fighting and you know actual physical contact. That's why all the Displays have evolved. You know, as an ethologist, you know you look at threat displays, you look at submission and appeasement behaviors because they don't want to fight. They do fight but you could be the highest ranking wolf or coyote or fox in a group and if you get injured fighting and you can't reproduce, then you know from an evolutionary point of view, you're genetically dead. So you kinda win the battle but you lose the war in terms of Passing your jeans on. So I think, actually say this to people a lot of dog parks just watch what these animals do, you know. Another thing is humans interfere in what appears to be something that could be dangerous and If you know dog you're fluent in dog you could be pretty efficient in knowing that something will or will not escalate into something that's dangerous. But you know, it's like with kids at some point they need to learn to resolve their own Social conflicts.

Speaker 1:If you will, potential social conflicts you mentioned a couple other words that are controversial sometimes in the dog training space, which are assertive and dominance, which will get to later in the on in the episode, will revisit those. I kinda want to pick your brain a little bit more to about when animals display a much higher level intensity of aggression so they might do much. Let's say, use a dog. That's much more likely to bite, with much more damage and from an evolutionary standpoint, from survival standpoint, that's not very efficient from, I guess, an ethology lens, right or not desirable, because you're risking injury to yourself and you know your fitness. So why do you think that occurs with some of the pet dog cases where we see significant levels of aggression, damaging death to another animal or even people, and maybe less so in nature?

Speaker 2:is that a correct?

Speaker 1:statement, or what are your thoughts?

Speaker 2:well yeah, I mean out in nature, if you will. You know, wills will kill other wolves, they'll kill intruders, and they can and coyotes to, though, and they can have really high intensity and violent fights within their group, but they also have the opportunity to get away. You know the individuals who are being attacked. I mean my take on not only home dogs, but even home dogs who go free, ranging, running around, cuz you know them boulder and there's lots of places where they can be free. You have great dog parks. Here is a lot of them just are chronically Stress, they're chronically anxious, they're chronically living in fear, if you will, not necessarily because of what their humans do, but just their daily routine. They try to do something and they're told no, they don't have any idea of what is permissible, if you will.

Speaker 2:So I think that that's one thing how they reared, you know, for rescue dogs and I know a lot of rescue dogs, I've had some rescue dogs you just don't know anything about how they were reared, their early periods of socialization, often none. So I've seen dogs at dog parks who came from the same litter, from a box on the roadside in New Mexico or Arizona or Texas, where a lot of dogs come from in colorado and even when they're three, four, five weeks of age there are very large differences in their personalities. I'm assuming they were all treated alike. So it shows that there's a lot of any inborn, inherent differences. But I do think that a lot of dogs have bad dog days, not intentionally, and you wouldn't even know it. You know what I mean, because it comes from people not understanding that these are fully sentient mammals, like we are fully most of us at least, are fully sentient mammals and their needs aren't met. Yeah, I mean, they're on edge, I really feel that way.

Speaker 2:And the dogs who I know I wouldn't say I know the best because I live in Boulder now, which of course is in a big city, but the dogs down here they can't run free.

Speaker 2:There's cars, you know some dogs are trained well, but when I lived in the mountains for years on end, the dogs on my road and the dogs who came down to say hello to them, they were almost never collared and rarely leashed and you know they'd have their spats. But generally I just never saw what I would see on an average day of the dog park or a hiking trail where they looked around and look to be always vigilant, always wondering, gosh, am I doing something wrong? Or you know, I really don't want to get in this particular dogs space, so I don't know of any studies, although I think that some of the studies that I know a free ranging and feral dogs Show that these dogs, yeah, they have their spats and yeah, they'll fight and yeah, they'll form dominance, relationships, social relationships within their group, but there's just not as much of the snapping and the nervousness, if you will.

Speaker 1:Yeah, yeah, I think you bring up an important point to. Something I implore a lot of my students to do is to observe dogs in different environments, their social interactions, so sometimes it's colored by our own. You know, lenses are looking at dogs, maybe just in our home or in a dog daycare or in a dog group class or so, observing dogs in dog parks and feral dogs running around on the street somewhere, and all because there's the differences sometimes are profound in their communication skills. Yeah, it's just fascinating to watch that.

Speaker 2:Right and it's a myth that these free ranging dogs don't form close relationships with people. I mean, there's been studies in Bali and other places and I've seen this in person in East Africa, china and India, where these dogs like people it's not like they're unsocialized, but their interactions are just very different because once again they've got the freedom to come and go. Yeah, when I was in southern India, I walked through the streets of the city from my hotel and sometimes I'd have dogs following me. Sometimes I wouldn't. I'd always have treats. I always give them food because they need the food. Some of them don't have regular Mealtimes.

Speaker 2:I just never felt concerned. I really felt like if a dog was trying to get in my face and I would just, you know, say something quietly like you know, leave me alone. No, you know, or go find another dog, whatever you know. Even if they didn't understand the English, I wasn't yelling at them and maybe they can sense that. You know they could sniff some of my fear, but they had the freedom to go somewhere else. That's excluding the cases where you've got dogs who have psychopathologies just like humans and Will attack you because that's just the way they've learned to adapt.

Speaker 1:Yes, yes, and I have this dream, someday mark, of doing like a world tour with a bunch of people like Ethologists and trainers, just observing dogs in different places. That's one of my favorite things to do when I travel. I go and I'm like don't show me this tourist sites, take me to where the dogs are, because that's what I want to see. I want to just watch the dogs because it's just so fascinating to me, you know.

Speaker 2:Well, I mean another experience I had and I and I was looking up the name just now and I can't find it and I think it still exists. But outside of Barcelona there's a dog rescue center and I'll try to find some more information. But when I went there there were about 200 dogs and there were separate. There were a hundred dogs in each enclosure. They were large but running free. When we pulled up there with my friend, we got out of the car and this Mass of dogs ran over to me and my friend, who was hosting me, said you'll be okay and they're okay.

Speaker 2:It just turned out that, yeah, when they first met one another, they would sniff, sometimes a growl, you know, an occasional fight, but it was incredible to me to see this group of one was a hundred dogs who just got along. Yeah, they snapped here, they peed here and there. You know, sometimes one had a bad day, but once again, you know, I think it's because they felt the freedom, two things the freedom to get away from something that could be really antagonistic and the freedom to find Dogs who wanted to sniff and play.

Speaker 1:Yeah, yeah so well, those that can envision all those dogs running up to you and it's like could be a nightmare for some, but a delightful dream for others. Right, well, I was.

Speaker 2:I was prepared for it. And likewise I've seen these big groups of dogs in India and outside in Nairobi, in Kenya, and you know some of them are in bad health. The people don't have that. They either don't get much care or the people can't afford it.

Speaker 2:But it's just kind of like, oh, who's this? Although they're not using English or Swahili, it's like who's this two-legged mammal who's walking in on me? You know, you get the feeling when I was out in the field for years on end with coyotes and sometimes with wolves, they're just looking, is like who's this two-legged thing walking over to us? But yeah, I think what you're suggesting is really cool. I I just really enjoyed being in these different places and having people say, well, there's this group and you know there's this reddish dog and he will run up to you really fast and stop and put his paw. You know so he's. The people would literally say he's not going to attack you. And of course, the first time they run up and they sit and they're like a low growl or snarl You're going. Well, I'm not sure about this, but but they were right.

Speaker 1:Yeah, you know. Yeah, yeah, it's so much fun to do that, I just love it. I would love to segue now to you. Emotions and animals. You know, because I know you've talked a lot about that today. You've written about it on psychology today, which I love, by the way, and anybody who hasn't seen Mark's articles there. Mark writes about everything from the sentience and animals, emotions, and even interviewed somebody about mushrooms, which is fascinating.

Speaker 2:So, so yeah, it's a great resource really.

Speaker 1:So here's a big question. You know, so you have some in in the world. That's where I will say you know, how do you know emotions? How do you know animals experience emotions? So what's your elevator pitch? For once, somebody says, mark, I don't know you. Yet how do we really know what a dog's feeling? Or how do we really know a dog's or an animal has emotions? Aren't they just sort of just responding to the stimuli in their environment?

Speaker 2:Well, there's a couple of questions there. At least is once you know. Number one do they have emotions? Do they have feelings, you know? Are they sentient? And of course they are. There's a dwindling number of people who wonder about whether dogs actually like playing, and I always say I'm glad I'm not their dog.

Speaker 2:That's, that's the answer for me. But you know, as an ethologist, so getting into the science, sometimes we have phenotypes like what we look like, what a dog looks like, the color of their fur, the type of fur, the tail, the ears. So phenotypes is basically the visible characteristics of an individual. But Conrad Lorenz, who won the Nobel Prize some decades ago, used to think of behavior as a phenotype. So he would talk about behavioral phenotypes and you know, the basis of that and the basis of ethology is careful observation. So just look at a dog. You know we're focusing on dogs. It could be other animals, you know. Look at how they adapt to different circumstances. They're flexible behavior. For example, they know they can do x, y and z with another one particular dog and a, b and c with another dog, and Some puzzle that they're putting together of what they can do with different dogs. Okay, it's also the case that there's just not very many phenotypes that just spontaneously appear in humans, for example. And so to me the question isn't if Emotions have evolved, but why have they evolved? What are they good for? Why are they adaptive? And I'm, you know, mixing emotions and feelings. I mean, you know, emotions are really the responses we have in our bodies. The feelings are the subjective expressions of these Things that are happening in our body. But I mean, when I start talking to people about that, I could see their eyes rolling and and and and I can. I feel very strongly that I could talk about feelings and emotions Synonymously. But there are a difference. But just look at it, an individual, and see how they respond. Like if you're looking at a dog, you know what situations are their tails high and wagging, or low and tucked under their butt? Well, where are their ears? Are their eyes open? Are they smiling? Are they snarling? Do you see little lip curls? Well, these behaviors that you could see are Sort of the outward indicators of what they're feeling. To me it's just not rocket science, but what I really like and I know this from my own writing that over the years there's just fewer and fewer skeptics that just are.

Speaker 2:From a biological point of view, it's impossible to imagine that the wide variety of responses that an individual shows could all be hardwired. If a do be, if see, do D, you know, and all that kind of stuff. The differences, the variation in the social situations in which, say, an individual dog finds themselves, you know, unless they're just stuck inside all day Under a couch. It's almost infinite. So they're adapting to the presence of different dogs with different personalities and that's based on what they feel.

Speaker 2:I mean, I can't think of any other way to say that yeah, and I think training techniques that are based on behaviorism, like stimulus response, things just don't work. I mean, you mean, they can work in terms of getting a dog to do what you want them to do, but then you've got a dog who has a very limited behavioral repertoire and who's living in constant, interminable fear, stress and anxiety. So you know I stress that to people that you know, yeah, you could do certain things with dogs, but because they are emotional beings, you can get them to do what you want them to do by Beating them or shocking them or doing whatever you do to them. But then you have like a with a kid yeah, they'll do what you want them to do, but the quality of their life is just horrific.

Speaker 1:Well stated. Yeah, and so there's different lenses of looking at emotions and animals and you're talking about from a biological perspective and an ethological perspective. Do you talk about effective neuroscience or a pancsep, for instance? Or include that type of view in your work as well.

Speaker 2:You know only to a limited extent because years ago I was in the PhD MD program in the neurosciences and I dropped out of it. So I Know a good deal of Yacht pancseps work. He was good friend of mine and we had disagreements about certain things but he did really solid research. So yeah, if people ask me about the neuroscience of what we're talking about, I can explain to them the little that I know. But you know, once again, in terms of the basis of emotions or feelings, you know we've got a lot of research on oxytocin, for example. You know the so-called love hormone.

Speaker 2:I mean, I think a lot of what people say about it is true, but a lot's overblown. You can't take a highly aggressive dog or cat or other mammal, say, and Shoot them up with oxytocin and think that it's going to be the panacea. You know. But I think what's really interesting for me is when I go to dog parks and I've been dog parks all over the place where there are dog parks you know, when you start talking about the neurobiology or the neuroscience, we have some really neat work being done on neuroimaging using fmri's magnetic resonance imaging on dogs, and what I like about it is the dogs have to be trained to go into, say, the machine. If they don't want to, then they're not used because, number one, you can't have any noise or motion.

Speaker 2:Gregory Burns, among others. He said emory, who have, who has done some of this work, uses his own dogs and he loves his dogs. So what I like about that research is that when you put a dog in a certain situation and you're creating a situation where they may feel a certain emotion, the same parts of the dog brain lights up as Human brain. So one of the studies this team did was looking at jealousy.

Speaker 2:Mmm and they created a situation where a dog see a dog getting another some food, say, but one dog was in the fm or our machine and Parts of the amygdala lit up because that's what MRIs look at is what parts of the brain are working and light up. And the same Parts of the dog brain lit up as would light up when humans express jealousy. Hmm, that's the form of affective neuroscience. What I like about those studies is that for some skeptics They'll say well, we don't know whether dogs feel x, y or z, but if the same part of the brain is lighting up, I feel comfortable Saying dogs feel that. You know, one of the holes in our data and and I think it's a huge hole is Alexander Harwitz is a really great dog researcher. Discovered that humans aren't very good at meeting a dog's guilty face. She never said the dogs don't feel guilty. I mean, I've written a lot on that, I've got quotes from her on that. So when people say, well, dr Harwood said the dogs don't feel guilty, I always say we don't know whether dogs feel guilty, I feel comfortable thinking they do. Their social mammals and a lot of other mammals, including, you know, non-human primates, feel guilt. But I would love to see some kind of situation where Some sort of affective neuroscience could be done, perhaps using the magnetic resonance Imaging. So I'm using that as an example Because for some of the skeptics, they want science, they don't think ethology is science, they think it's stamp collecting, which, of course, one of the dumbest things I've ever heard of my life.

Speaker 2:But for some people who questioned whether dogs felt jealousy I just know this from having people write to me the study on jealousy and looking at MRIs convinced them that dogs do feel jealous. I mean, when I talked to some of my friends and I go to dog parks and I say, well, what do you think about dogs feeling jealous or guilt, they go. You academics got to get out of the ivory tower and into the field, if you will. But I think your question is a really good one, mike, because it's closing the door even more on the skeptics who say, rather than saying we don't know where the dogs feel something, they say dogs don't feel something or can't feel it. I mean that's the proverbial putting the cart before the horse. We don't know. Yeah, so I feel very comfortable. Yeah, I mean, I don't doubt dog dogs feel jealous and I don't doubt, dogs feel guilt. But you want to be a scientist, go do the work.

Speaker 1:Yeah, yeah, highly agree. Yeah, we're gonna take a short break to hear word from our sponsors and we're gonna come back and talk more about emotions, and especially with its relation to aggression as well as dominance. So we'll be right back. Hey, friends, it's me again and I hope you are enjoying this episode. You may have figured out that something I deeply care about is helping dogs with aggression issues live less stressful, less confined, more enriched and overall, happier lives with their guardians. Aggression is so often misunderstood and we can change that through education, like we received from so many of the wonderful guests on this podcast. In addition to the podcast, I have two other opportunities for anyone looking to learn more about helping dogs with aggression issues, which include the aggression and dogs master course and the aggression and dogs conference. If you want to learn more about the most comprehensive course on aggression taught anywhere in the world, head on over to aggressive dog comm and click on the dog pros tab. And then the master course. The course gives you access to 23 modules on everything from assessment to safety, to medical issues, to the behavior change plans we use in a number of different cases, including lessons taught by dr Chris Pockel, kim Brophy and Jessica Dolce. You'll also receive access to a private Facebook group with over a thousand of your fellow colleagues and Dog pros all working with aggression cases. After you finish the course, you also gain access to a private live group mentor session portal with me when we practice working through cases together. And if you need CE use, we've got you covered. We're approved for just about every major training and behavior credential out there. This is truly the flagship course offered on aggression and dogs, and it's perfect for pet pros that want to set themselves apart and take their knowledge and expertise to the next level, or even for pet guardians who are seeking information to help their own dog. And don't forget to join me for the fourth annual aggression and dogs conference, which is happening online and in person from Chicago Illinois, september 29th through October 1st 2023. This year's lineup includes many of the amazing guests you might have heard on the podcast, including Sue Sternberg and dr Tim Lewis, dr Christine Calder, sindor Bangal, cyrus strumming, sean will, masa Nishimuta and many, many more. Head on over to aggressive dog comm and click on the conference tab to learn more about the exciting agenda on everything from advanced concepts and veterinary behavior cases to Working with aggression and shelter environments and even intra household dog dog aggression. And I want to take a moment to thank one of our sponsors for the conference.

Speaker 1:As a family of world-class trainers, fense dog sports Academy provides expert and accessible instruction for competitive dog sports using the most progressive training methods and positive reinforcement techniques. Through their online platform, students are able to access professional dog training, no matter your location or pup skill level. Fdsa believes the bond between the dog and human is a proud and life-changing Partnership and they'll work with you to develop a respectful and kind relationship with your furry best friend. Check out FDSA at FENSE dog sports Academy dot com. All right, we're back with dr Mark back off. We're gonna jump into emotions now and aggression in the relation to aggression. So I'd love to hear thoughts on which emotions Results in those emotional responses of aggressive behavior. Obviously, fear we were talking about fear is one of them. Perhaps we can jump to things like rage or anger.

Speaker 2:For again, looking at the effective neuroscience, you know system of it, or just your thoughts on that, in terms of what you're seeing with aggressive responses in animals, yeah, I think it's the same as we would say in humans it could be fear, feeling anxious, being uncertain, which of course is tied into fear, could be a dog just having a bad dog day, just like humans have bad human days. And when I first wrote about that some people just laughed and I went well, why would you laugh? I mean, dogs can have bad days. I've lived with dogs who get up in the morning and they're gnarly. They're not typically gnarly, but they have a short fuse. And If I did something or said something or went over to hug them a, pet them the dogs who liked being hugged or petted I Could tell that they weren't comfortable. So they could be having just a bad day. You know they could have had a nightmare. I guarantee you that other animals have nightmares. You know, like other animals dream and they dream very vividly. So my take on it is number one it could be a chronic condition for an individual dog, as I've seen in the field with coyotes and foxes, for example, where they're just, they're nervous all the time something happened to them. I mean, I suppose it could be innate, I just don't know enough about that, but they have longer or shorter fuses and it could be just tied into context.

Speaker 2:But when people say, well, no, dogs don't really feel these things, or they don't use these behavior patterns to form, say, social dominance relationships or Whether there are alpha dogs, they're wrong. They're just wrong. The notion of alpha and the idea that there's no such thing Was really a misreading of some studies on wolves. One of the major ones is there was research by a guy who's mr Wolf, if you will. I mean, maybe there's people now who know as much as Dave Meach he was, you know. But I wrote a paper 13 to 15 years ago and Dave's had been a longtime friend of mine and I asked him about that and he wrote back and said, no, the people in the dog World have misinterpreted what he said. He even uses the words alpha and dominant, you know, in his paper.

Speaker 2:So I think for me it's a misreading of what dominance is. So it doesn't have to be fighting, it doesn't have to involve you know, any kind of physical Contact. I could dominate you by walking towards you and having you Change the route that you're taking. That could be a form of dominance. So dominance could be simply defined as Mark does something that changes Mike's behavior and you avoid me. You could be smelling me. If I'm a dog, you could be reading my approach, but you do that in humans. I mean, I have avoided walking near people who are strolling up to me in a very stiff gate or they're looking around and their facial expressions look really nasty, so dogs can read that and dogs have the advantage which I'm glad we don't of maybe smelling a assertiveness or dominance. So I think part of the misreading is that dominance has to involve fighting or really intense threatening. It doesn't.

Speaker 1:Yeah, I have a number of questions I can go down but so I wanted to give a little context for the listeners too, because I think some of the audience may not have heard of the concepts you're talking about or have certain conceptions about it. So we're saying dominance exists, and that's an interesting thing is that sometimes in some of the conversations in the dog training community it's put out as oh, there's no such thing as dominance at all. But especially from the field of ethology it's a very known phenomenon and so if you were to give sort of a definition that you would put out there for, like, the dog training community in terms of defining it, I know you kind of explained it in that sense of an example, but because what we actually usually see is priority access to a resource, so that's the one term of it.

Speaker 2:Well, that would be the yeah, and really I'm not nitpicking, but that would be the effect of there being some kind of dominance relationships between two or more individuals that grants them priority of access. However, I mean with the dogs I lived with and all the dogs who used to come down to my house in the mountains, I would have to say that there were no quote dominance relationships among them. It was first come, first served. They liked one another, they played. I mean I use them as an example, as I do some of the dogs I met in India and China and East Africa, where they might have subtle dominance relationships that I couldn't read, but they knew one another well enough to say, oh yeah, mike's over there eating, so I'm not gonna bother him, I'll avoid him. Maybe it's because you snarled at me before, things like that. Like I said before, I simply think in a generic and very general way, that you could define dominance as being one individual controls the behavior of another individual. So there are shades of gray, there are shades of dominance. If I walk to you and you walk away from me, I've controlled your behavior, but then I could say, oh, did you avoid me because you thought if we interacted or crossed paths that I might threaten you and you could say, yes, I did, or you could say, oh no, I didn't. I saw something across the street. So that gets back to how powerful ethology is in looking at context. At least I can say to you Mike, did you avoid me because you thought I was gonna beat you up or steal your coffee? You can go. Oh no, I didn't even think about that. I was looking across the street and I saw a squirrel. Oh, I saw another friend.

Speaker 2:I think this is really important and that's why the dynamics at dog parks and talking to the people, the dogs, humans, is so powerful. Because they'll say I'll get there and maybe I don't know the dogs as well as I should or could. I shouldn't say should, but there's a lot of dogs and I'll ask people. I say, well, I see Molly and Rose. They've got this kind of dynamic where Molly seems afraid of Rose and the people go no, she's not afraid of Rose at all.

Speaker 2:10 minutes ago, rose had a stick and was running around and didn't wanna share it and Molly tried to get it and Rose growled at her and then 30 seconds later they're rolling on the floor playing so to me and I've got this book coming out called Dogs Demystified one of the most important things people forget about it's easy to forget about in home dogs or dogs you don't know is context. So once again I'll go back to Wild Canids Wild Wolves, coyotes, foxes. You see this all the time. You get out there and you spend an hour watching them and you think you know all there is. And I always tell people, after eight and a half years and thousands of hours watching wild coyotes, I was still learning things about them, as was my postdoc and research team. So I'm not saying that we can't learn anything, but we need to be really careful about jumping to rapid conclusions.

Speaker 1:Yeah, yeah, I wanna unpack this a little further too.

Speaker 2:Sure sure.

Speaker 1:So we're using those examples. For instance, so Mark gets in my space because he wants my coffee or something like that, so he has that particular context and that particular moment. We say, mark, as dominant behavior resulted in Mike saying, okay, you can have my coffee, and so that's that context, that moment. And then I might learn from that too. I might be like, oh, that last time Mark gave me that look and I gave up my coffee. So the next time I'm gonna avoid Mark when I've got a coffee or he's got a coffee. And so there's that learning experience too. But it's also fluid, right. So there's another day where I have my pizza and I give you a look and you are like, ooh, mike's really giving me that dominant look. So it's very fluid.

Speaker 2:He's resuiscarding his pizza.

Speaker 1:So with that, that would be, I guess, a fairly accurate description of moments of dominance and the relationship happening there, or context.

Speaker 2:That's a great example In the absence of any threat or any physical interaction. So I've talked to people who and I can understand there they would rather reserve the word dominance although I don't think it's factual for situations where I'd actually approach you and threaten you or push you, or a dog would jump on another dog. But that's what I think is wrong, because so many people who say dogs don't express dominance it's just wrong. There's no mammal of whom I'm aware that doesn't set up some kinds of relationships. You've got highly social elephants, for example. But even within a herd they learn who they can approach or not, or when they can approach another animal and not piss them off.

Speaker 2:I've seen this so many times at dog parks. I mean it's just going there and seeing the same dogs over and over and over again and then going with somebody who doesn't know these dogs which I've done with students and they'll say, oh, rosie is dominating Molly and what's going on. And I'll say, well, you know, like Rosie's human told me, no, there's no dominance there, it's just they don't want to share this toy, or Rosie tried to get the toy and Molly didn't want her to have the toy. I mean there's just, there's so many things going on and once again I get back to that. That's what's so exciting that you know it's no one size fits all explanation and I'm not a dog trainer, but I love when dog trainers and some of whom I know around Boulder use all that information to come up with an effective curriculum, if you will, to helping a dog along.

Speaker 1:Excellent, now a little further in packing. So we were talking about contexts, right, and so we sometimes also see applications of relationships or also that alpha term, right? So in a, let's say, we use an example of a home with four or five dogs and they have different moments of all. Right, today I'm going to have access to this bone, tomorrow you're going to have access to that food bowl, and so on and so forth.

Speaker 1:So we see these different relationships in certain contexts, but sometimes they apply sort of overall umbrella oh, that dog is the most dominant one all the time or that dog is the alpha, which is, you know, a problem for a lot of trainers because the argument is very loose, relationships or fluidity and gray areas and so what are your thoughts? On that. Does that make sense?

Speaker 2:It makes a lot of sense because I think the word alpha is it's misused or maybe the best way to say it it doesn't imply what other people think or some people think. If I'm alpha over you, it doesn't mean that I'm beating you up every time and you're avoiding me all the time. It's that somehow we have a relationship where you, I know that I can get away doing certain things to you, but it would reach a point where you might say no way and you could come after me. But it's also you're recognizing that relationship and saying, okay, that's fine. I mean, if you're looking flocks of birds and groups or packs or you know whatever you want aggregations or herds of mammals, you'll see that. So alpha might mean that I have more freedom of movement, when in a group, for no reason other than I, have more degrees of freedom and I can move around more than, say, you can.

Speaker 2:So the main point I think that's coming out of this and I've thought about this for so long is there's no doubt that dogs form dominance relationships. I mean, if you look at studies of free-ranging and feral dogs, we know that there's no doubt that there are higher ranking Alpha dogs. But you need to be really careful of how you use the term. That's all. So when people say there are no alpha dogs or dogs don't form packs, yet dogs form packs. I mean, I had a student who studied feral dogs and they do form packs and a lot of the packs resemble wolf packs or coyote packs. So I actually think sometimes and somebody asked me this a few weeks ago whether it just comes down to being very careful on using umbrella terms that imply different things, and I think it is yeah. Yeah, so do I use the terms? I use them, but I always editorialize them.

Speaker 1:Because I think one of the issues in the dog training industry anyways is that applying the Principles of the misconception of the term to dog training. So instance somebody says I need to be the alpha in my relationship with the dog, but then they incorporate punishment techniques or abusive techniques in the name of that right precisely.

Speaker 2:You could be the alpha using force-free, positive training, but the term alpha doesn't seem to really apply there. If you will, although you are, you're saying I want you to do something, but I'm gonna teach you to do it in a way that doesn't mean that I'm dominating you, but in the sense you're controlling their behavior. That's why there's so many shades of gray and that's why when people say they don't exist, I mean to me that's in the same ballpark of sorts like saying well, dogs don't feel guilt, you know yeah, and stuff.

Speaker 2:I Think it's really important because I know people have called me who have gone down to the local shelters around you know Boulder, where I live, or other places and they see descriptors of dogs and They'll always ask the people say, at the shelter or the rescue center, who know the dogs, what do you mean by this term? And Thank goodness, the people at the shelters or the rescue centers are really well educated and they'll say well, we're using that term because in these situations, this particular dog Feels uneasy and can be assertive or pushy and and we know dogs can be pushy yeah, yeah, they get paid to sometimes push us to see what they can get away with. But I find that to be really a lot of fun.

Speaker 1:Yes, see, this is why I love this conversation, because we're in packing terms that are sort of four letter words in the dog training industry. But they're four letter words because some people have taken them and used them to Justify very forceful or punishment based techniques to dogs. Right, and so that's the disclaimer neither Mark or I are advocating for. Punishment in the name of dominance, or you know, talking about alpha right.

Speaker 2:Well, I'll tell you what's really interesting for me. I was just looking something up that I had written about this, but I can't find it. It's okay, I don't think. Maybe it was between, say, 10 and 15 years ago that I actually came across Statements that said dogs don't form dominance relationships and there's no such thing as an alpha individual. I mean, that's pretty Late into my long career, if you will, but it blew my mind and Then when I started to, or tried, if you will, to have discussions with these people, they wanted nothing to do with me.

Speaker 2:They told me I didn't know what I was talking about. There's a lot of things I don't know, but I knew what I was talking about from just being a long-term carnivore Ethologist. That's when I first learned and I actually called some dog trainers you know, I called teachers, whatever, but dog trainers and Honestly, they too had the same response, saying whoever it is that saying this has no concept of what's going on. It also turned out that some of the people who were saying it were people who used forceful techniques so they could be the dominant or the alpha or the leader of the pack, which to me makes just Zero sense. I'm sorry, it just Makes no sense at all.

Speaker 1:Yes, yes, yeah. And it's a shame because, unfortunately, when certain terms or labels are used in our industry, we avoid those conversations, those deep, meaningful conversations that need to happen to understand those terms you know the terminology involves. So it's a shame that that happened, because there's such a learning opportunity. You know, in 15 years ago, especially when this we were really talking about it.

Speaker 2:I Agree and disagree to some extent.

Speaker 2:The people I've tried to talk about don't want to hear from me and I don't want to hear from them, so understand so it knows so, in all honesty, it's like First amendment you have a freedom to do what you want and say, and I have a freedom to do that. So, but it's the same kind of situation with talking about animal emotions or personalities. You know, you reach a point where you have a conversation and an hour later or a week later, you're having the same conversation and I'm not going to change and that are going to change. So good, go do what you want to do. But the reason I'm very careful about this with dogs in particular, because you could talk about it, about Wild wolves or coyotes or chimpanzees or elephants, but the people who disagree with you have zero impact on the lives of these animals, the wild animals.

Speaker 2:The people who disagree with you have on the ground Interactions, perhaps as trainers, with dogs, and so they're bringing their ideas into the curriculum, if you will. Yeah, to me that's just bad news. I mean, I hate to say it that way because I mean it's no surprise that I'm a fan of positive force, free training and you know all the upsides and to that kind of technique. But that's what I was thinking about just a couple of weeks ago. It's funny, I was finishing this dogs demystified and reading some sections on training and you know I just was reading your stuff and other people's and Realizing there's still people out there who are gonna read that and are gonna be Really upset when you just say, look, there's no reason to hit a dog, shock a dog, yellow, that you know what I mean.

Speaker 2:People say, well, have you ever yelled at a dog you were living with? No, yes, I have. But I mean I have to say, did I notice a change in their behavior afterwards? No, they knew I love them. But you know you've done it with people where you just go. Stop that. But I do think in the world of dogs these kind of overarching statements there's nothing such as or believing. There's no such thing as dominance or aggression or assertion or happiness or joy. Just it spills over into the way people interact with them and when they're trainers, results in Pretty bad treatment of the dog.

Speaker 1:It certainly does.

Speaker 2:I mean I'm not. I don't mean sorry in an apologetic way. I, I just had it.

Speaker 1:I mean I, I just can't do that, yeah, yeah, and it stifles Curiosity as well when we say this thing doesn't exist and then our mind shuts off oh, I guess it doesn't exist because somebody saying it doesn't exist. So let me move on to other things, without being curious about these things that we sometimes don't even understand yet. So it's a shame when that happens, right?

Speaker 2:Well, it's a shame when it happens. And it's a bigger shame Because the downside as you know much better than I do is dogs get abused and people don't interpret it as abuse, but it is abuse, sorry, I mean, you've got a fully sentient feeling being there who wants to trust you and wants to have a life where there's agency, mutual trust, mutual respect, and they don't. But then people say, as you know much better than I, well, what I did works, they heal, they listen to me and I'm going, yeah, and they're probably in a chronic state of stress Because they're afraid. They're afraid that if they don't do what you want them to do, you're just gonna hit them again or shock them would do whatever you know, whatever your aversive technique Consists of and I don't want to know about. I mean I, I, I have to say that I don't want to know about it.

Speaker 1:And what a great waiter kind of wrap up what we were talking about. All it just all ties together and really understanding that dogs are sentient beings with lots of emotions. So you're talking about a lot of that in your upcoming book. Do you want to talk more about that?

Speaker 2:Oh, I would love to. The book is called dogs demystified an A to Z guide to all things canine. So it's different topics. There must be 800 of them. I think maybe some got dropped in the copy editing but my brain was so filled that I wouldn't have known or maybe cared. But it's laid out alphabetically by topic. There may be a few topics that someone would think about that aren't there explicitly, but it's all covered. So it's descriptions, lots of stories, it's all science-based and the references will be on my home page when the book is published, so people can just go to the home page, click on a reference and there it'll be, which I think it's really convenient because you don't have to then either copy and paste a URL or type it out, which we used to have to do, and of course they could be 45 characters and you miss one.

Speaker 2:But the book is really based on Wanting people to respect dogs for who they are contrasting home, free-ranging and feral dogs becoming fluent in dog or dog literate. I'm really excited about it. It really ate me up, if you will. I mean I I've really been working for years on it and about a year and a half ago Somebody said to me you should write a book like this, and I I've been trying to avoid it. Having edited three encyclopedias when, where I had people contribute, you know I think it'll be a very useful guide in a very Conversational way. It's really written in a conversational way but based on science and common sense, an ethology and solid biology. So people can go oh, I want to know what the word aggression means, or abnormal, or caching, or lip curl, or I blink because of me. So I'll just.

Speaker 2:The book is almost an ethogram of 300 pages, but what I love about it too, I've got numerous stories that have come to me over the years, from not scientists necessarily, but people who Say what's going on here? Or tool uses, an example where people used to say, well, no, years ago Humans were called homophobes, which mean man the tool user. But then, of course, jane Goodall discovered tool use and now we see it and it was just coincidental. I was writing the section on tool use, I had a few stories and within that week so it was almost cosmic that people wrote me. I got four or five stories of different dogs using different objects as tools. So yeah, there we go.

Speaker 2:And you know, years ago I said it would blow my mind if dogs didn't use tools. I mean, we just haven't seen it. Do dogs recognize themselves? How do they use Female? We call it in our book unleashing your dog. So I'm excited about it and I'm hoping people will read it and send me stories. And somebody said, oh, will it be a second edition? And I went no, but Unlikely. But what I like about it is on my home page. I can put these out and people can have access and then write to me with more stories. I'm excited because it's kind of like an open forum and we need that. We really do. Yes.

Speaker 1:Yeah, I'm excited for that. I'm very much looking forward to it as well. It should be out at the time, at the release of this podcast episode. So if you're listening and now, you should be able to get the book in Expecting somewhere in June.

Speaker 2:I think Mark said so yeah, I'd say by mid-June Perfect, and it's gonna be a relevant. I mean, I'm really thrilled that it's gonna be a relatively inexpensive paperback, which I really like, because you know academic books with 150 pages of References, which this could be, could cost 45 dollars. It's a field guide, I mean, that's another word that you know you could apply to it. What I love about it too, is I sent out.

Speaker 2:At one point I regretted it just because I was getting comments back left and right, but I sent out a lot of the entries both to science colleagues and to people who sent me stories, and we actually have a section there of what would you like to ask your dog. So I've got a lovely story from Paul McCartney of the Beatles about a dog he rescued. The singer Joan Baez did the original drawings who's, and Emmy Lou Harris, who's a very well-known singer. She runs a rescue center for senior dogs. People don't know that these quote famous people are really into animals, but I also have my neighbors and my cycling buddies Saying this is what I would like to know from my dog. So once again, I think the open format ultimately will really Result in a lot of information and I can send it to you, mike, and you can write a book on it.

Speaker 1:I will 100% take you up on that offer, or we could do it together but yeah, so anyway. Mark, thank you so much for coming on the show. I really appreciate your time in your expertise.

Speaker 2:This was wonderful, so I hope to see you again in the future likewise, thank you for letting me free will, because we know a lot about dogs now. But I always say the more I know, the more I say I don't know. But once again I come back to it because it's why I wrote dogs demystified. It's the practical, on the ground application of what we know about dogs to getting them to adapt to a human world. You know, even free-ranging and feral dogs, maybe to a lesser extent, have to adapt to a human world. But we are a human dominated world and we're asking dogs, maybe especially home dogs, we're asking them to do things that are not dog. I mean, it's very simple.

Speaker 1:What a way to wrap up your shows. Thanks again, mark. I appreciate it. My pleasure. Thank you, mike. What a way to wrap up this season. I'm just so fortunate to have this opportunity to chat with so so many incredibly talented, knowledgeable and passionate people in our community, and Mark certainly did not disappoint. I'm looking forward to diving into his latest book and hearing more from him in the future, and I want to especially thank you for listening in and supporting the show. I couldn't do this without the wonderful support of so many listeners from around the world. So thank you and thank you for all you're doing to help the dogs in your life. I look forward to launching season 5 with more incredible guests, and I hope to see or hear from you at one of the next aggressive dog comm events. And, as always, stay well, my friends.

Speaker 2:He's resource, guarding his pizza.